Michaela Pavlátová Looks Back

Under Communism, animation evaded Soviet censors when live-action and documentary film could not. Animator Michaela Pavlátová recalls a period of great artistic freedom, which may come as a surprise

It is September 2024 and I am lucky enough to speak to Oscar-nominated Czech animator Michaela Pavlátová for The Skinny ahead of a screening of Eastern-bloc animated shorts at Samizdat Film Festival, Scotland’s first festival of Eastern European film which also celebrates the cinema of Central Europe, Central Asia and The Caucasus.

In one of my favourite ever interviews, Pavlatova generously tells me all about what it was like to produce animated shorts under Communist rule: How, contrary to what you might think, many factors led to it being a time of great artistic freedom that Pavlátová looks back on with fondness amidst all the grey. Thanks to Jamie Dunn, The Skinny’s Film Editor, for his permission to reprint the feature with this new introduction and minor changes hereafter.

Graduating from art school under communist rule in Czechoslovakia, Michaela Pavlátová’s recollections of her burgeoning career in animation represent what it was like for many of her peers in the countries that found themselves politically, militarily or otherwise aligned with the Soviet Union in the latter half of the twentieth century: A time when the government’s hand meddled strongly with documentaries and feature films, going so far as to ban some films in their country of production while simultaneously distributing them internationally for festival acclaim (which is what often happened to the work of one of Pavlátová’s contemporaries, Czech surrealist Jan Švankmajer). “Yet, somehow, they didn’t expect anything dangerous from animation,” which led to much weaker censorship, she tells me.

As a result, animated shorts such as Pavlatova’s Řeči, Řeči, Řeči… (Words, Words, Words) survive as artefacts of untouched creative freedom in a way that live-action studio films do not. Not only that, but they are also relics of a time when short films had state support the likes of which we rarely see now, and an audience ready to receive them.

At the time, all feature films shown at the cinema were preceded with a short state-funded film that was either documentary or animation, “[So] it was part of all our lives,” she says. “We didn't have so many choices [as we do now]... But somehow people were more into culture, because if there was a book out, all people read it.” People lived their lives locked in privacy, especially when a piece of Western media made it through the iron curtain. They held secret screenings and book groups. In this hybrid culture of ravenous cultural appetite and the stifling uniformity of the regime - of grey streets, grey clothes and empty shops, as Pavlátová recalls - animation was a “small, positive island of freedom.”

For most of us raised with that pervading image of the Eastern Bloc as a pallid and desolate landscape, the news that it was a place where animation was thriving may be hard to square. Compare that with conditions in 2024: Under capitalism, which promised so much when the Berlin wall fell, the animation industry is in disarray. Those working in Hollywood VFX describe a race to the bottom, where studios bid to work for minimal time and pay. Artists are leaving in droves, putting their sleep and their mental health ahead of the visions of executives that are frankly uninspiring anyway. Closer to home, like in Prague where Pavlátová is Chair of the Animation Department at FAMU, students at the world’s fifth-oldest film school are graduating into an almost non-existent market for their projects.

It was of course a far-from-perfect place to come of age. Even as the Communist party’s hold over everyday civilian life began to loosen under Perestroika, Gorbachev’s ill-fated reformation movement, higher education was far from a meritocracy. Raised by parents who weren’t in the party, Pavlátová was only allowed into art school because her uncle was an artist and knew people in the commission. It was also a confusing place from which to set off on newly-permitted trips to Germany and France as a graduate. She recalls sitting on trains and being petrified by the threat of a stranger injecting drugs into her arm, so strong was the state propaganda back home.

Yet her films were not overtly political and so she was practically never out of work. Pavlatova doesn’t remember any deadlines, nor studio notes, when she started making professional shorts in 1987. So long as she could keep producing films to occupy the slot before the main feature (reserved in the West for adverts and trailers), she was left pretty much alone, save for the studio’s in-house script-doctors, editors and animators who were ready to work at her disposal should she need them. After the Revolution in 1989, everything changed. The studio continued on its last legs for five years before new owners took over and stripped it for parts. “They were not interested in producing non-profit films”, she says.

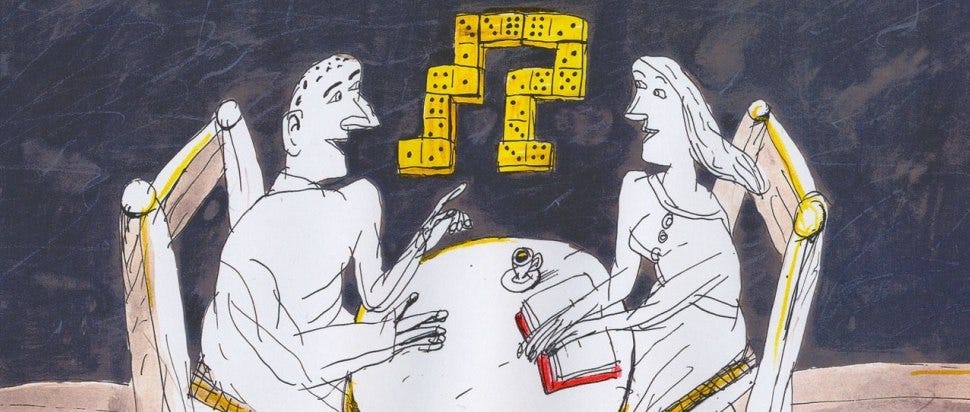

It’s in this twilight period for the studio that Pavlátová’s Words, Words, Words was released. It survives as the product of a bygone age. Its experimental choice to portray the dialogues of coffee-shop patrons solely visually - as all different shapes and symbols: lighting bolts; question marks; dominoes and puzzle-pieces - is unlike anything being produced in the mainstream animation landscape today, reserved as it is for the latest crowdpleaser from Disney, Dreamworks or Illumination.

But given the wealth of independent creators sharing their work online nowadays, Pavlatova appears hopeful for the future. Her experiences have taught her that “mainstream also produces people who don’t want to make mainstream; that mainstream actually produces very big fans of art films.” Through sheer force of will, beautiful and groundbreaking works are still being made in makeshift spaces. And festivals such as Samizdat are helping them connect with their audiences. “They are small groups of people, but those people are hungry to see something different,” she says, smiling.

Samizdat Film Festival will return in early October 2025, with events in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and other locations in Scotland. Submissions are open now until June 2025.