James Albon's Love Languages

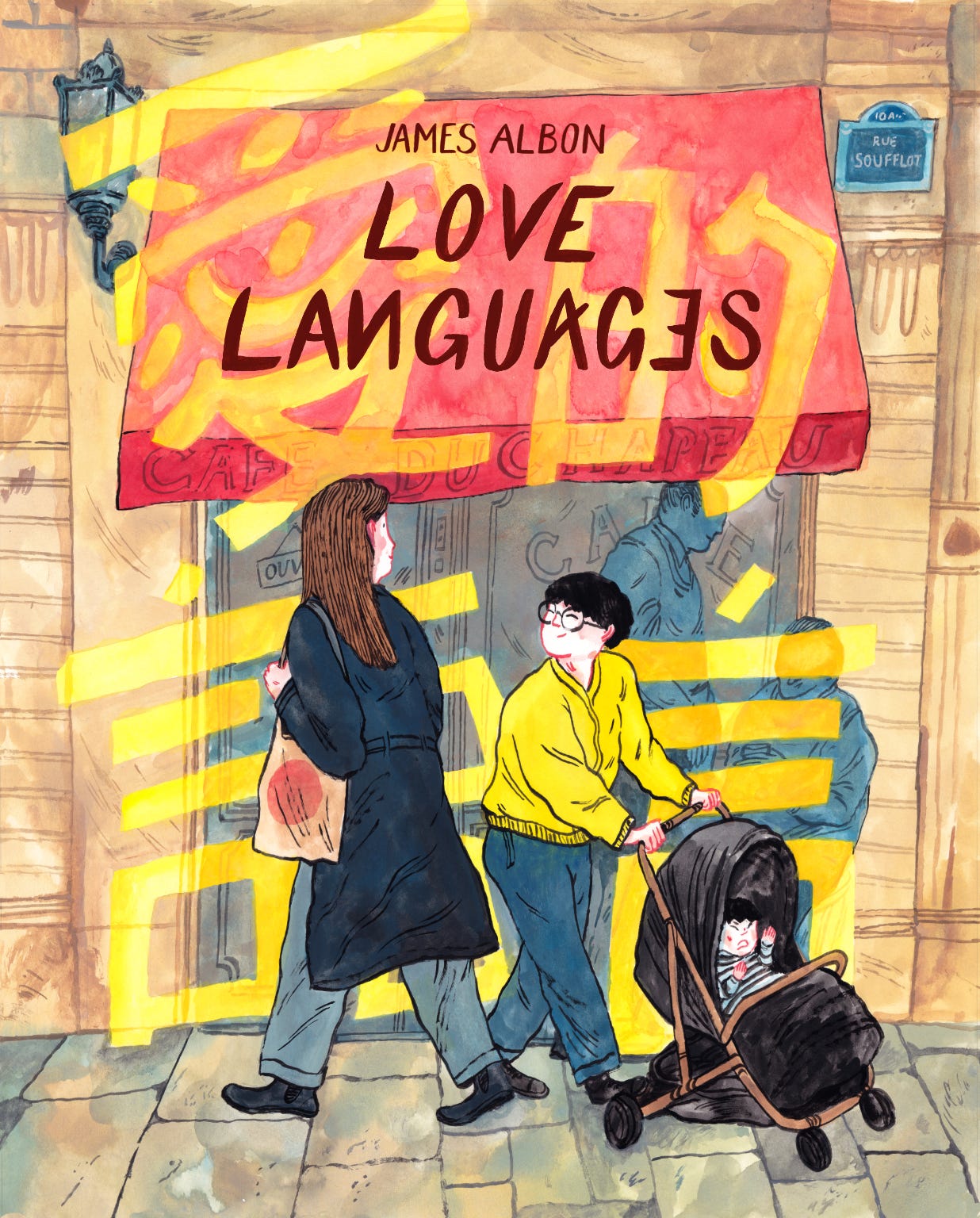

James Albon's fourth graphic novel celebrates the world-expanding potential of learning a new language

When someone has as distinct an art style as James Albon, it’s possible to spot them in a crowd from their illustrations alone. Case in point, when I bump into the Edinburgh-based illustrator at a flea market, I recognise his work instantly. I just have to tell him how much I loved his 2021 work The Delicacy. Notebook in hand, Albon is manning a stall which he has decorated with drawings in his unmistakable hand: playful, fluid caricatures that recall European bandes dessinées by way of classic New Yorker magazine covers. This is one of the great things about Leith: Between the Drill Hall on Dalmeny Street, where artists like Jack Stamp produce and exhibit work as part of Out of the Blueprint’s risograph printing residency, and the specialist Franco-belgian bookshop La Belle Adventure on Leith Walk, it’s a hub for local comic book illustrators.

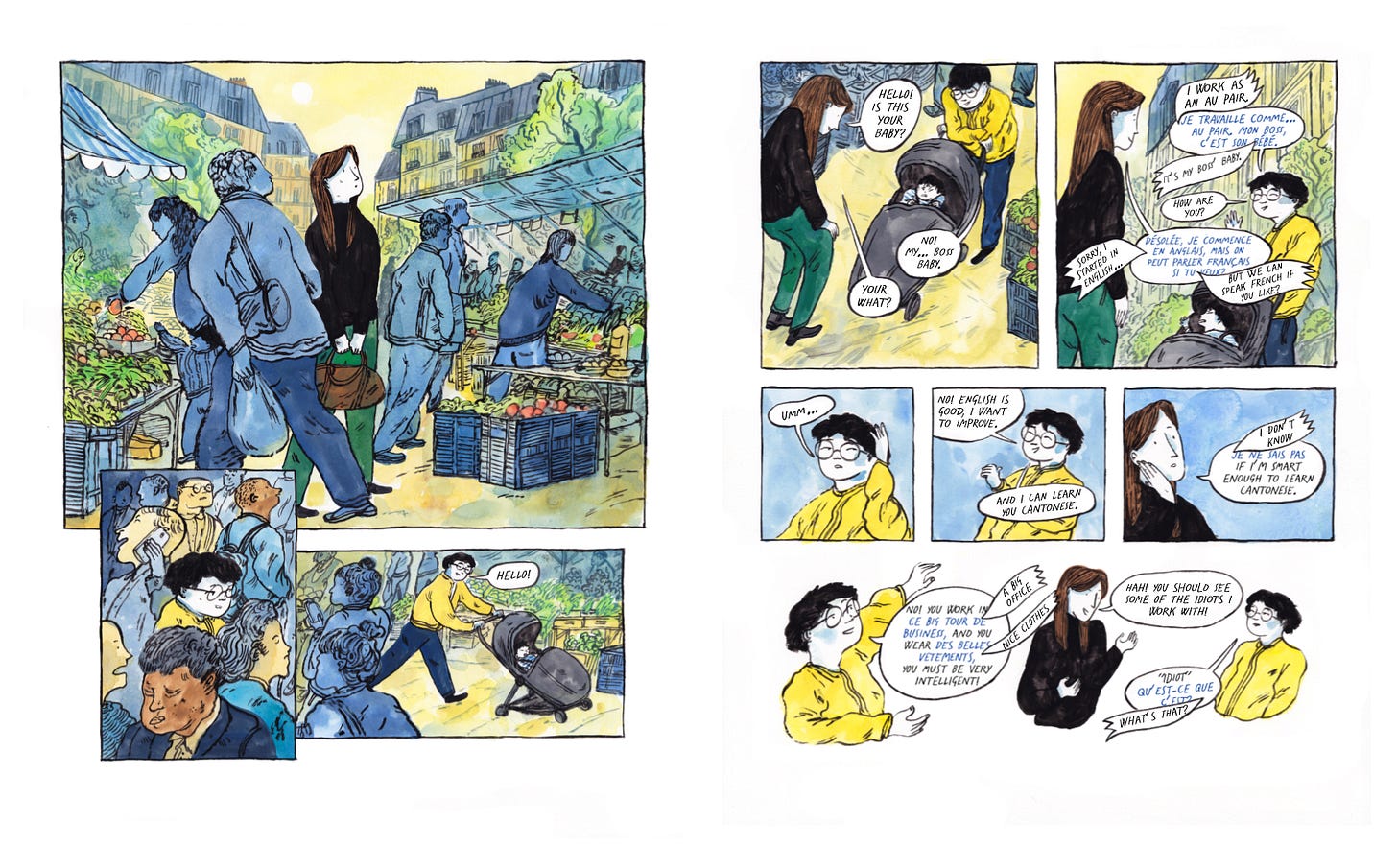

A couple of weeks later, Albon and I are in a nearby coffee shop chatting about his newest graphic novel Love Languages. The story follows Sarah, a Brit working a high-powered corporate job in Paris and struggling with the isolation of it all. When she meets Ping, an au-pair from Hong Kong, things start to look up. Driven by a shared need to improve their French, the pair meet over informal language lessons in the city’s many parks, galleries and cafes, during which they also flit in and out of their respective mother tongues of English and Cantonese. But their friendship quickly develops into something stronger; something for which words fail them irrespective of the language in which they search for them. That’s about as spoiler-free a description as I can probably give, so if you want to go in completely blind, I invite you to stop reading. However, given that the book is called Love Languages, the discovery of a burgeoning queer romance will doubtless come as a surprise.

Albon’s journey to becoming the polyglot he is now (with near-fluent French and Cantonese amongst a handful of other languages he is currently practicing) started surprisingly late. It began with an apathy towards modern languages that is typical of every UK secondary school student. He did standard-grade French until he was about 16. “Or [rather], I was physically made to sit in a French classroom for two hours a week… But I did not learn any French at all,” he says. “I hated it. You’re given textbooks from the Eighties and you’re just like, ‘this language is dead, nobody speaks it.’” It wasn’t until his hometown was paired up with a village in France on an exchange programme that it even occurred to him that the language existed beyond the page. “There were French teenagers in this village! I was like, ‘What? Nobody told me!” he says. Suddenly, he had a French girlfriend and a reason to learn French.

Years later, meeting his wife, Cat, who is half Scottish and half Hong Kong Chinese would kickstart his Cantonese lessons and form the inspiration for parts of Love Languages, which also takes details from his friends Poppy, Chao and Taika, to whom the story is dedicated. Introducing a queer element into the mix for his graphic novel, which was not a part of his real-life inspirations, came out of a desire for a slower burn between his protagonists, however. In real life, Albon’s friends may not have been able to speak to one another but their mutual attraction was clear to them both. For Sarah and Ping, the dynamic needed to be different if he was to sustain a dramatic narrative: There needed to be an element of mystery. “The linchpin of the book,” says Albon, “is [the question of] how do you ask somebody ‘are we more than just friends?’ in a foreign language or in a patchwork of several languages. Had they been a straight couple with this obvious physical connection, that would take the tension out of the question.”

As a straight man, he had natural reservations about telling a story that was not from his own lived experience. Would he be able to approach it with the nuance and authenticity it deserved? But the story, of two women who initially identify as straight and whose self discovery is concurrent with their improvements in language learning, was the perfect metaphor for what he wanted to express: That when we break down barriers of any kind, we discover things about ourselves. Gradually, he was able to relax into it for two reasons: One was his friend Hannah, a queer artist who acted as an unofficial sensitivity reader; The other was the reminder that there is no such thing as a single, monolithic queer experience. “So it was really about coming up with unique characters and then giving them a unique relationship,” he says.

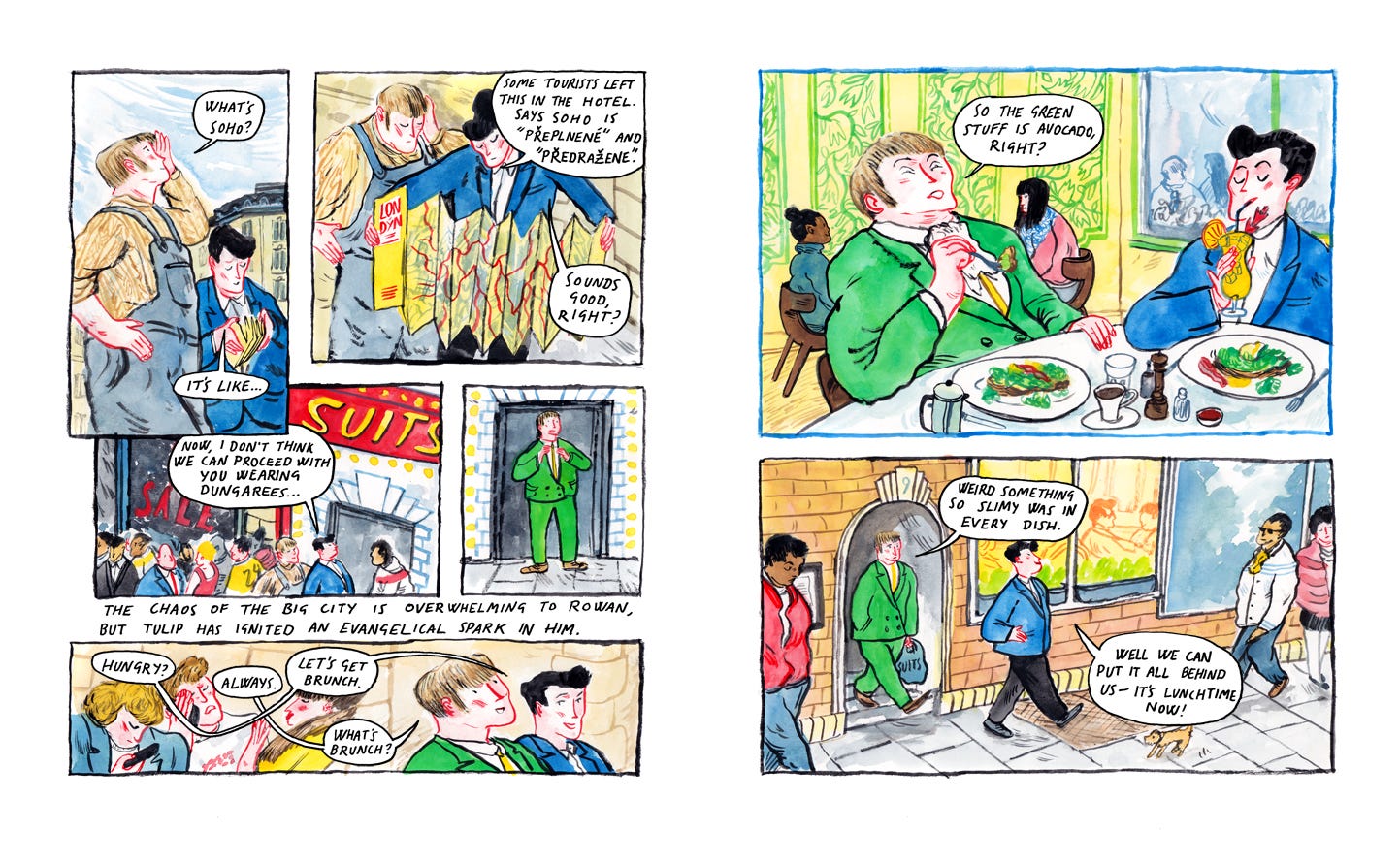

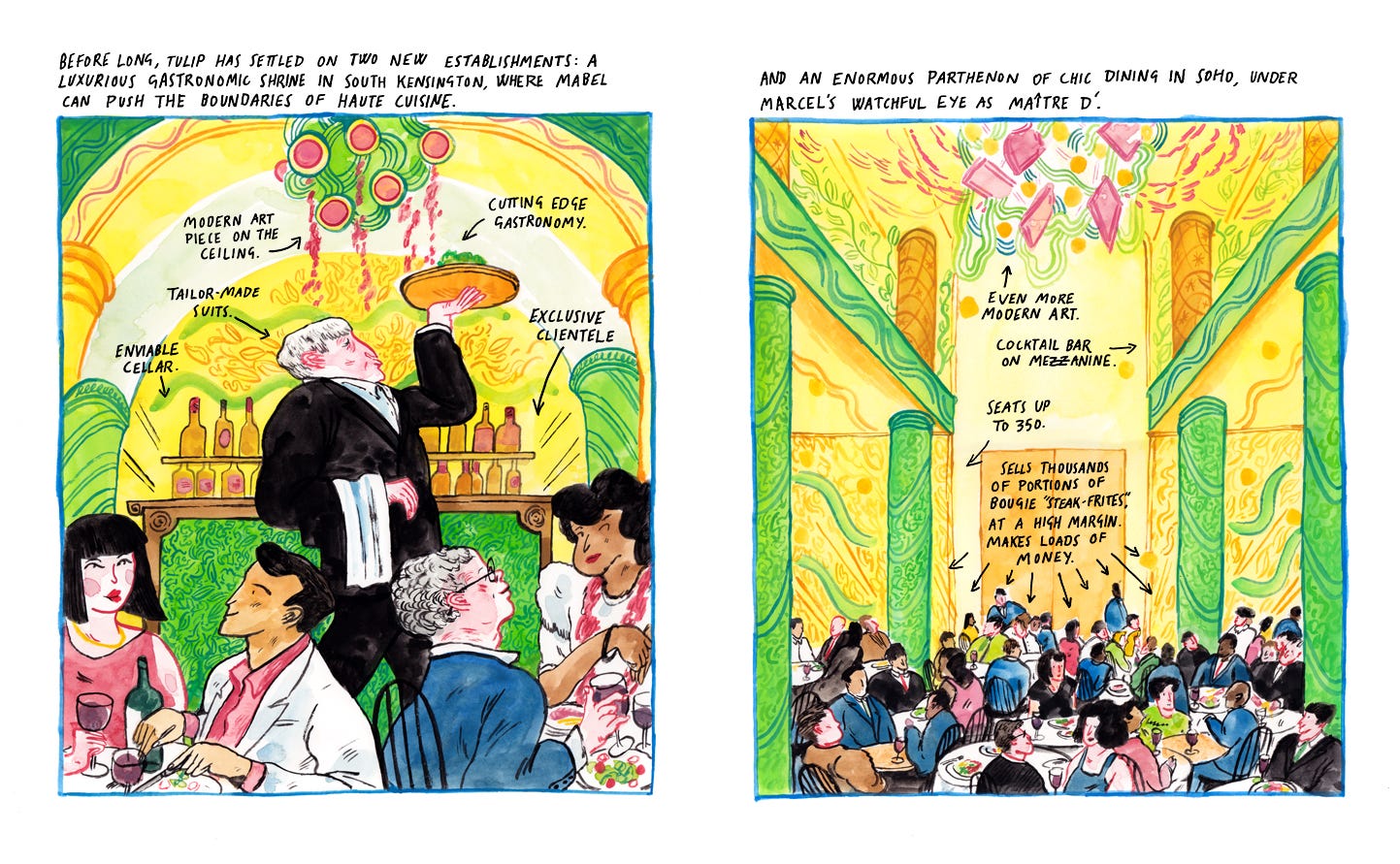

Finding and sustaining tension is what Albon considers the key to writing all of his stories. For his previous work, The Delicacy, he found it in the opposite personalities of a pair of sibling restaurateurs. When brothers Rowan and Tulip find success in London’s fine dining culinary world, Tulip’s dreams of celebrity and expansion are at odds with Rowan’s more modest ambitions (This is, again, as spoiler-free a version as possible). It’s a tried and tested technique: Give your characters conflicting dispositions and the conflict takes care of itself. He cites the classics, to which he often returns when he’s in the process of crafting a story: Shrek; A Knight’s Tale; Peep Show. They’re useful exemplars because, unlike, say, The Godfather (“Which, firstly, is extremely boring, and secondly, it’s so dense has so much stuff going on that it’s hard to piece apart,” he says), their narrative structures are so simple and the films wear their artifice on their sleeve. Be it Shrek and Donkey or Mark and Jez, their desires and viewpoints – and, crucially, where they clash – are obvious.

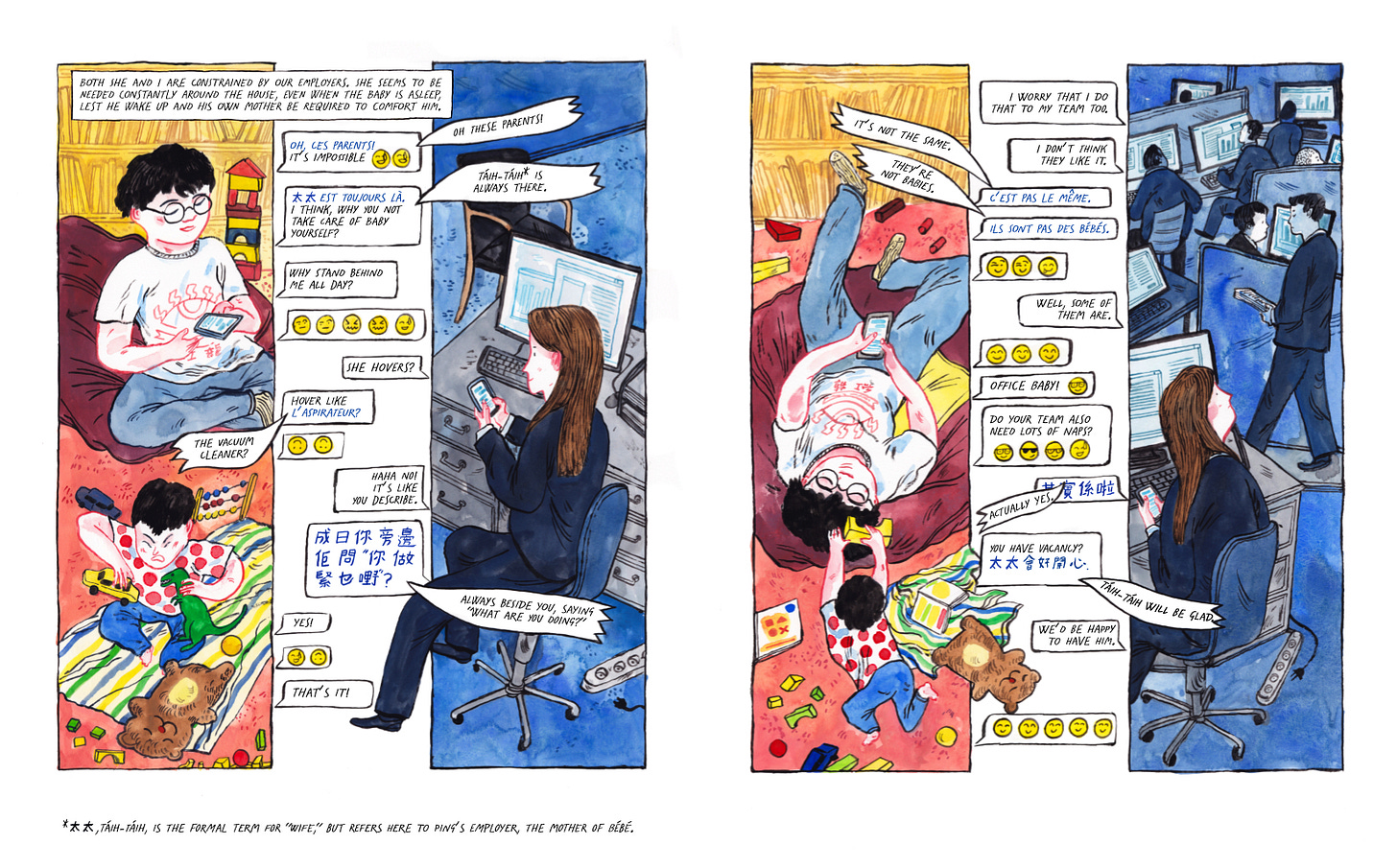

These were key texts when he was writing Love Languages, as they were for his previous works, but a joke from his wife Cat drove him to challenge himself. “‘Do you think you can write a dramatic story where [spoiler alert] nobody dies?’ she said,” says Albon. The result was this new story in which the characters are not so much in conflict with each other but with, “First of all, themselves,” says Albon, “but also the language barrier, and then – and this is the driving force in all of my work – Capitalism.” Sarah’s job is at the centre of all her problems in Love Languages: Isolation; fatigue; low self esteem. Scenes in her office are some of the book’s funniest yet horrifying. Men throw out buzzwords but ultimately say nothing at all, leaving the reader wondering just what it is she does. Ping, similarly, is at the beck and call of her employer who outsources their childcare onto her. Ping and Sarah fit their not-quite-dates around these conflicting schedules, making the necessary compromises familiar to anyone who has had to balance the giddy early-days of a relationship with their job. The conflict may be less immediately dramatic than murder, but it’s hugely, compellingly true to life.

Adding to the book’s realistic texture are the generous hand-painted tableaus typical of Albon’s work. In Love Languages, he perfects his detail-filled top-down spreads that fill out his characters’ personalities through their choice of books, furniture, posters and the like. They transport us into Sarah and Ping’s interior worlds. Albon works in a mixture of watercolour and gouache, a mix of media he arrived at gradually. His first book was done in coloured pencil, though it still bears the signature look he would go on to nail down. He cultivated the look over years of study at Edinburgh College of Art and then at London’s Royal Drawing School. Despite the fact that the RDS nowadays proudly list him as an award-winning alumni on their website, he remembers feeling penalised at the time for his desire to draw comic books rather than opting for a more traditional Fine Art route. When I point out the similarities between the expansive, storytelling qualities his work shares with the oil paintings you might find in monograms of the Old Masters, he responds that it’s precisely the oil paintings that they wanted. “They weren’t happy with a similar concept expressed as a double-page in a comic book. It’s very contextually specific in that sense” he says. Undeterred, he handed in a graphic novel as his final project at The Royal Drawing School: A book called Her Bark and her Bite, which established his ongoing relationship with his publisher Top Shelf Comix.

Having come to reading comics relatively late, he had spent the last year discovering the works of Marjane Satrapi (Persepolis) and Jillian Tamaki (Boundless). By the time he was working on his second book, Shining Beacons, about a Soviet-era illustrator commissioned by the state to paint the central mural of a swimming pool, he was sharing a studio in France with a bunch of animators whose mastery of watercolour and gouache paints inspired him to adopt them. He says, modestly, that he “still can’t do a good job,” in comparison to their precise work, but that that’s part of the fun: “It’s important to be surprised by your drawings,” he says. “You can’t be too rigid in your expectation[s].” To his humble self-assessment, I counter that it’s precisely his gestural, playful strokes that add charm to his images. His work captures the world around us, in that it is made up of happy accidents.

For the hodge-podge conversations running through Love Languages that flow between English, French and Cantonese, Albon had to come up with a system that – as far as he knows, at least – is an original invention. Ping and Sarah may content themselves with only understanding every few words, but an English reader needed to be able to understand everything without prior knowledge of all three languages being a pre-requisite. After a long period of sketching various methods and options, he eventually landed on a combination of two systems: One where two languages share the same speech bubble, differentiated by ink colour; The other, overlapping speech bubbles where the translation partially obscures the original language. It’s an innovation that may take some getting used to but is essential to experiencing the story through Sarah and Ping’s eyes (or rather, ears). Seeing as his previous books have been translated into French, it will be interesting to see how a translator tackles the challenge of making them work for a new market.

At its core, Love Languages is a love letter to the world-expanding possibilities of opening yourself up to a new language and, in any cases, whole new ways of thinking. Albon is a believer that it’s never too late to learn; that, contrary to popular belief, our capacity for languages never really wanes. “There’s this myth that a baby’s brain is magically, neurologically better at learning languages,” he says, “but as an adult, if someone could recreate the conditions in which a baby learns a language, like if you could take four years out of your job [to just learn] and anytime you made a mistake, people were just unrelentingly lovely to you, you could be fluent in Mongolian in four years,” he laughs. Of course, for an adult, things aren’t that simple. We have our priorities: jobs, our dependents, our leaky faucet or bathroom that needs retiling. Sometimes it takes something undeniable, something like desire, to break through all of that and remind us that more is within our reach. And who knows what we might discover about ourselves in the process? Finding out that our limits are moveable might just open us up to new ways to see, to hear, to love.

Love Languages is out now via Topshelf Comix. A talk and signing with James Albon is being held on Sunday, May 24th, at La Belle Adventure in Edinburgh. Read my 5-star review of Love Languages at theskinny.com.

I'm adding it to my reading list! Glad to see that comics scene of Edinburgh is flourishing.