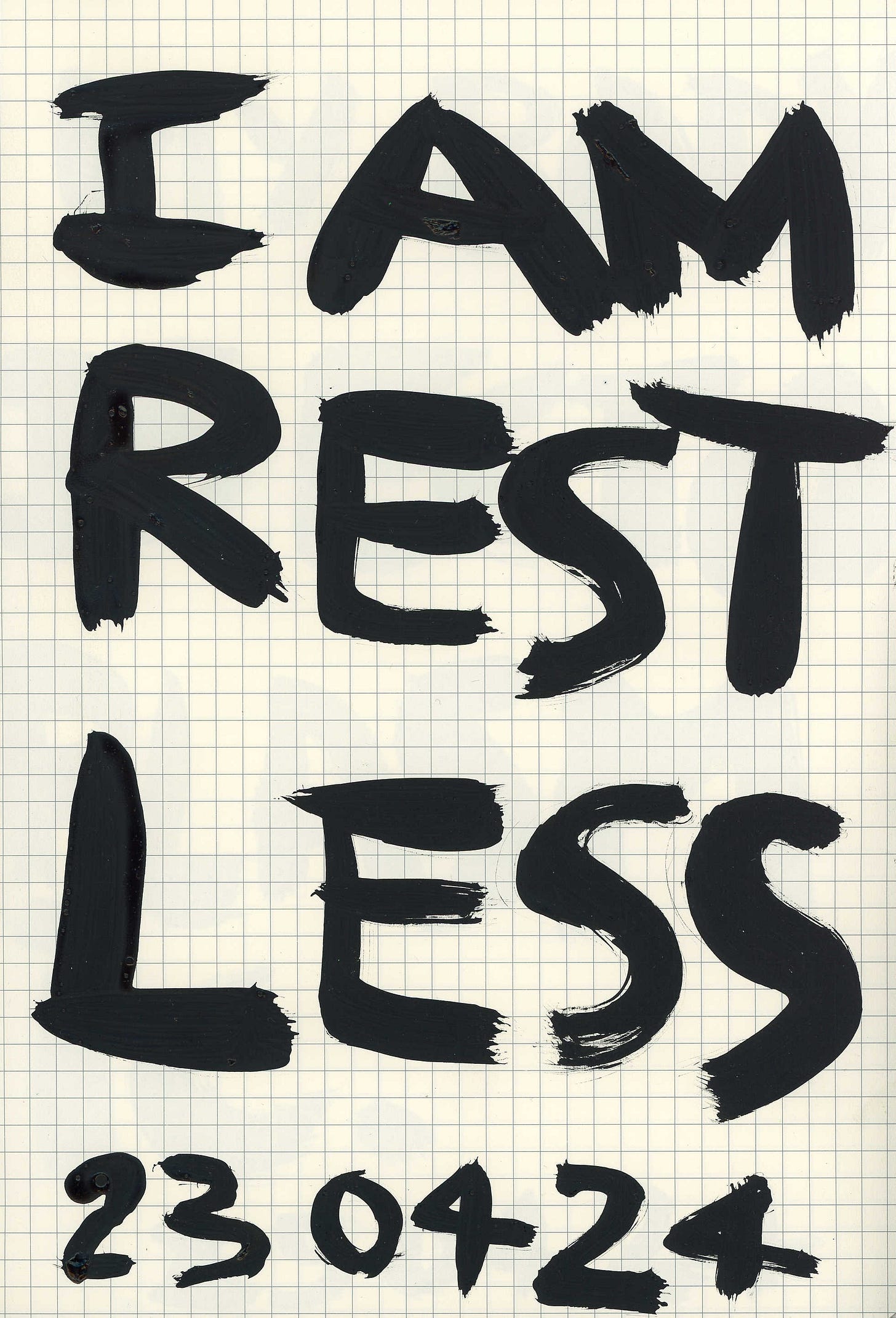

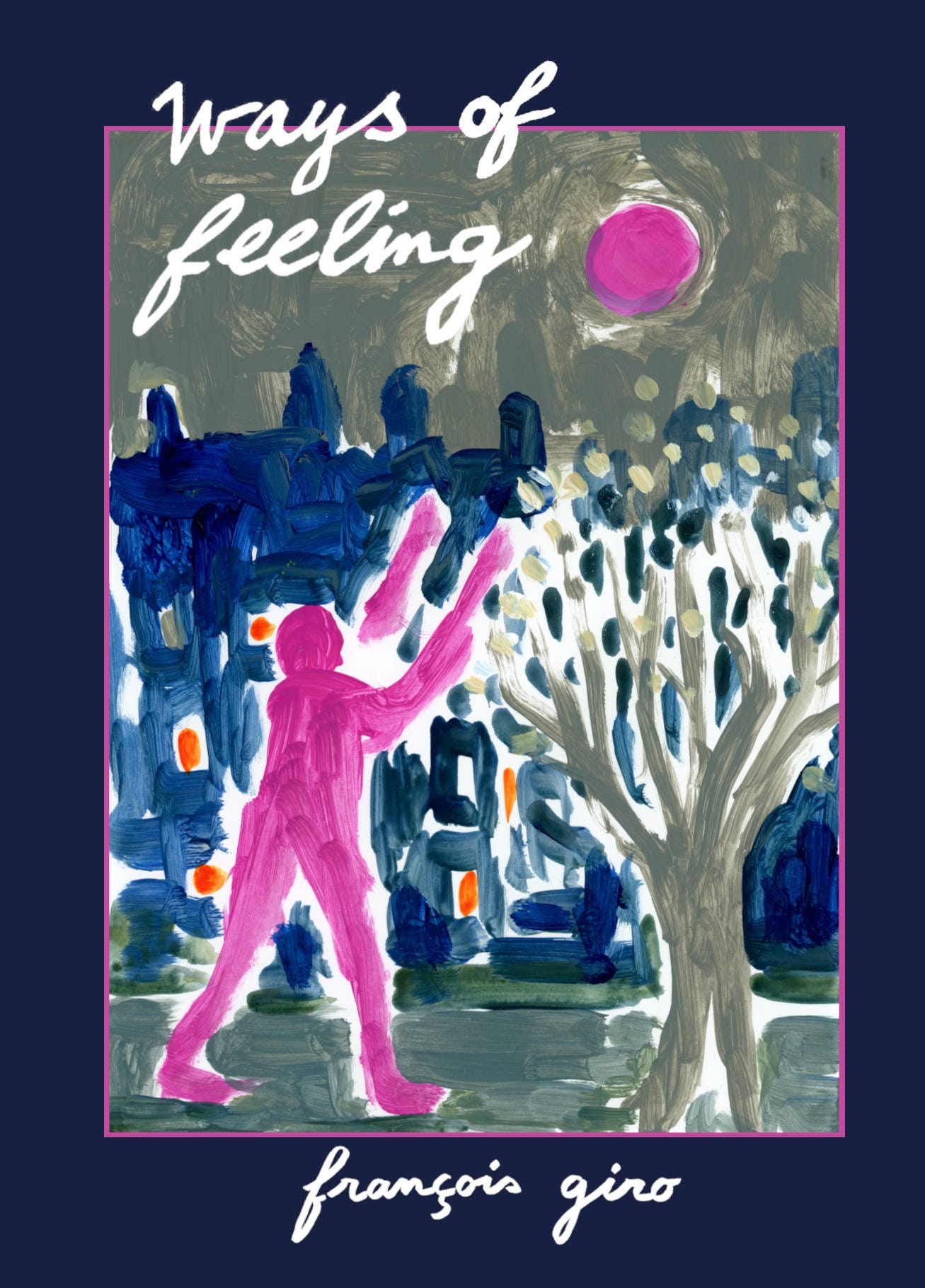

Francois Giro's Ways of Feeling

Francois Giro expresses the power of noticing our inner and outer worlds in ‘Ways of Feeling’, his fifth volume of drawn diaries

Early on in Francois Giro’s Ways of Feeling, he draws himself watching Tsai Ming-liang’s Rebels of the Neon God. When I first came across the Edinburgh-based artist’s drawn diary, only a day or 2 had passed since I watched my first ever Tsai Ming-liang film: 1994’s Vive L’amour. It was a funny coincidence. Here was Tsai, a director whose work I had never seen before last month and whose hypnotic images of urban ennui were still swimming in my mind, when suddenly the visual journal of a stranger appeared at my door and referenced Tsai within its first few pages. It felt like a moment of synchronicity. Here were two works of art that expressed something similar.

In a 2012 New Yorker article, Tsai Ming-liang’s work was characterised as cinema that highlights “the power of attention.” His characters are often alone and in motion, saying very little but imbued with an intense melancholy as they ride their mopeds through Taipei, or sit quietly on strangers’ beds, or walk through an unfinished park in the early hours of the morning. Like Tsai Ming-liang’s, Giro’s work is characterised by a gentle, attentive eye that is attuned to the world around him. He started his daily drawings over 2 years ago now, which have culminated in 5 volumes.

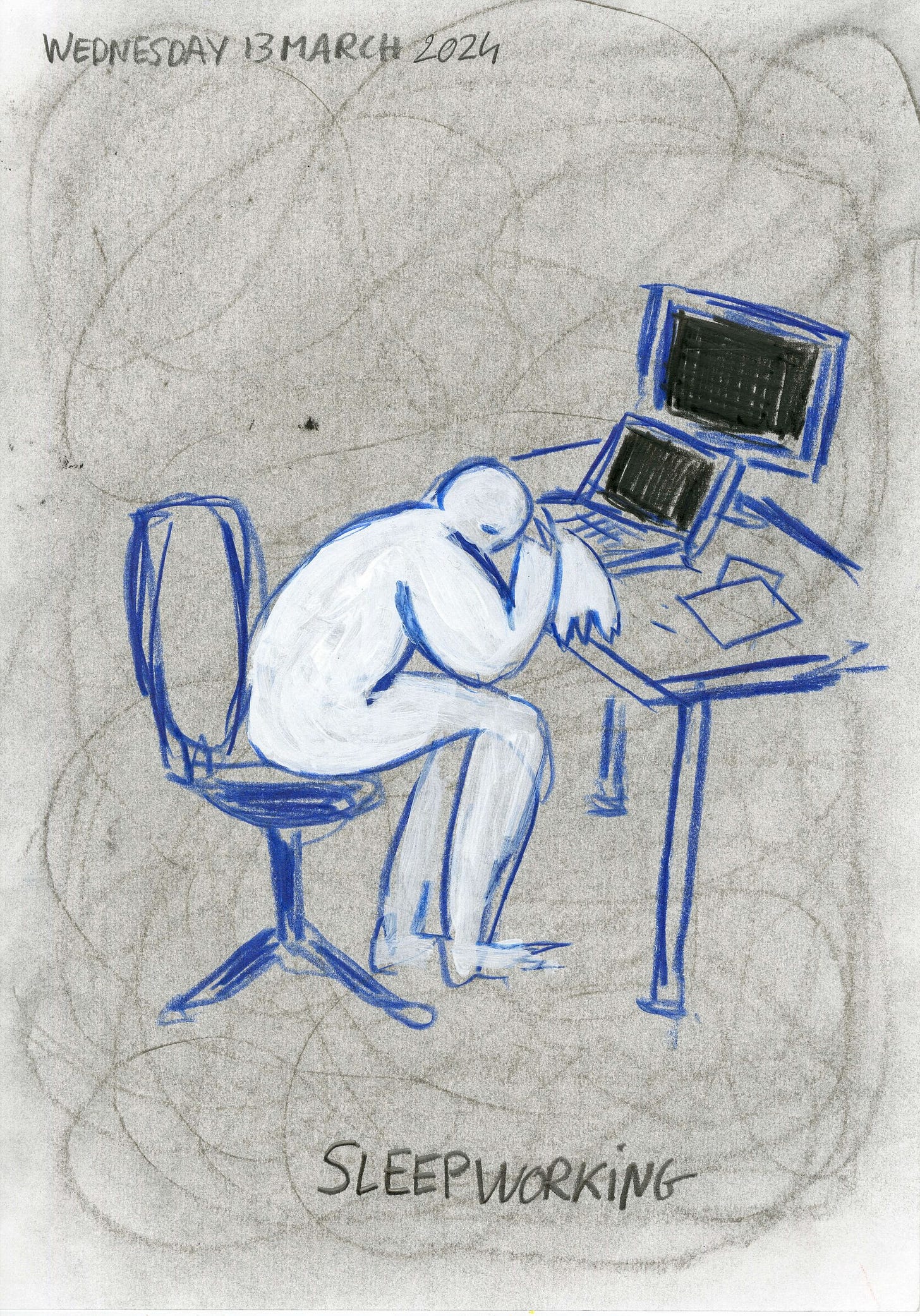

His latest, Ways of Feeling, centres on a figure who we often see walking off a work day or taking a break from the complicated silence of isolation. It is Giro, but an amorphous version. Drawn in as basic a way as possible, the world around him — by contrast — swirls. The swirls are made with ink, watercolour paint or coloured pencils, depending on the day. They give an indefinite, ever-changing quality to the narrator’s surroundings. A representation of Giro’s underlying anxiety, perhaps. He was certainly in the throes of it when he started volume 1.

When we meet for coffee, it is because he DMed me on Instagram. Having seen that I review books, he wanted to send me a copy of his. It was my idea that it be the first post on a new substack. He tells me that volume 1’s early drawings were “much more saturated” than they are now. “Quite dark in a way.” At the time, life in lockdown felt insurmountable. Drawing — his first love and something that he had been trying to reacquaint himself with for some time — would go on to be a lifeline. Aged 12, he was sure he was going to be a comic book artist. At school in France, he would rally friends to start writing stories with him, inspired by the likes of Regis Loisel and his dark Peter Pan adaptation. But those never really got beyond 2 or 3 pages. “We accumulated lots of beginnings of stories,” he says.

At 18, his interest in film took over. Now, at 33, he is teaching the subject at the University of Edinburgh, having completed a PhD. Throughout his 20s, he continually tried to keep drawing, knowing that it helped him express himself. But his inner critic was too loud. Working from photographs, he could never see past the mistakes. And then as 30 was approaching, COVID struck. Unable to go anywhere or do much of anything, something began to click. He drew every day and found a looser, quicker style towards which his inner monologue wasn’t quite so fierce. He ditched the photos, drawing from observations and memories instead. For the first time, he wasn’t drawing “for the dream of being a successful author. It was much more existential.”

“That’s something that really interests me,” he says. When it’s “not about skills or [making money] but really about reflecting on your life and society. [About] your discomfort with the world you live in, and how drawing can help your mental health. It can help you live in a better way, notice things.” No wonder reading his diaries has such a calming effect. In my view, they capture something universal. We are all guilty of forgetting to notice things once in a while. Whether we’re engrossed in our work, in our phones, or whatever else. But then that first ray of Autumn light hits our window, or that smell of wet concrete hits us as we’re leaving the house one morning, and we remember to stop and take it in.

A few years ago, the BBC did an adaptation of junior doctor Adam Kay’s book This Is Going to Hurt. I had loved the book, but found the series a hard watch. The events were the same, but reading Giro’s diary made me realise the difference was this: In the show, Kay is in the action. He’s asleep in his car, then rushing into A&E, then onto the maternity ward. Someone needs his help. Now he’s blocking the door. A clipboard is being thrust into his hands. It was too much. The book, on the other hand, was his diary. Every time you read it, you knew he was in the quietest, most contemplative moment of his day. You instantly relaxed. He could talk about the chaos, but he wasn’t in it anymore. He could put a shape to it. He could give equal weight to the emergency he had been dealing with and the pithy putdown he’d thought of but had to suppress at the time. Suddenly, as a viewer, you felt a little bit more agency over your own life too. You were reminded that we’re all — no matter who we are — allowed a break.

Journaling gets a bad rap sometimes. Most recently, by the author Colm Tóibín on the Adam Buxton podcast. “[Scoffs] Writing all about yourself? And setting it down and closing it and thinking that’s the truth? That seems, to me, the opposite of therapy,” he says dismissively. And, okay, yes, maybe there are diarists out there who engage with it in that way. People who never question their version of events. People who bitch and moan about their loved ones, centre themselves as the unerring protagonists of their lives. But Giro’s diaries couldn't be further from Tóibín’s weirdly snobby view of journaling.

Giro’s captions contain questions, not answers. He is constantly questioning, not just his version of events but the very power structures he (we) are all playing into on a daily basis. ‘Can love be a form of resistance?’ he asks as he draws himself in the arms of his partner, the words ‘The fiction of success’ and ‘The pressure of capitalism’ written on either side of them. ‘The first intuition / It’s not necessarily the truth / But why do intuitions feel right? A few marks on paper / Not much,’ he writes a few pages later.

The title Ways of Feeling came from Giro looking up at his bookshelf and at the spine of a book he has passively taken in countless times: John Berger’s Ways of Seeing. It’s a book that examines how we interpret visual art. But what about how we interpret life to produce that art in the first place? “[Ways of Feeling] isn’t only about seeing,” he says. His drawn diaries are the products of an ethos he has arrived at gradually, as he has learned to love drawing again. “It’s about feeling. Not about the photographic reproduction of reality, but about what drives and interests you.” With drawing, as with life, “not overthinking it is very important,” says Giro.

Francois Giro’s Ways of Feeling is out now. Order it at francoisgiro.com.